HARTI Policy Brief 2025 : Evaluating the Impact of Entrepreneurship Development Programs on the Progression of Agro-Based Startups in Sri Lanka

Background

Sri Lanka’s agricultural sector, employing nearly one-fourth of the labour force, remains central to rural livelihoods yet continues to struggle with persistent structural constraints such as low productivity, limited value addition, weak market integration, and high vulnerability to climatic and economic shocks. Over the past two decades, the government of Sri Lanka has increasingly promoted entrepreneurship development as a strategy to modernize agriculture, diversify rural incomes, and address rural youth unemployment and post-crisis economic pressures. Multiple agencies now operate entrepreneurship development programmes (EDPs) aimed at skill development, technology transfer, and enterprise facilitation.

Despite this proliferation, the sustainability of agro-based startups remains low, with many enterprises stagnating after initial support. Evidence from previous literature and field actor’s points to fragmented institutional mandates, unclear targeting, input-driven support, and weak follow-up systems as key contributors to poor outcomes. The current study was conducted to bridge this evidence gap and provide a rigorous assessment of how government-assisted EDPs affect agro-based enterprise progression.

In line with national development priorities, including agricultural modernization efforts, youth enterprise promotion, SME growth strategies, and the new push for rural entrepreneurship, the study evaluates the structural and functional effectiveness of existing EDPS and proposes a strengthened operational model for future programs. Findings are directly relevant for policy actors who are working with the focus of agro-based entrepreneurship development, while it could also be beneficial for others who provide diverse services in relation to entrepreneurship development in Sri Lanka.

Methodology

Combined quantitative and qualitative approaches enabled capturing the multi-dimensional nature of entrepreneurship development. Kurunegala, Nuwara Eliya, Badulla, Kegalle, Hambantota, and Matale were selected to reflect agro-climatic and socio-economic diversity. A structured survey was conducted with 310 agro entrepreneurs who had participated in government EDPs within the past three years, to collect data on business performance, entrepreneurial traits, and the nature of support received. To assess causal relationships between program attributes, entrepreneurial characteristics, and business outcomes, a Structural Equation Modeling (SEM) was applied. Key informant interviews with policymakers, program officers, and technical experts provided insights into institutional logic, operational gaps, and implementation practices and enriched a rigorous and context-sensitive assessment of the effect of structural and functional dimensions of EDPs on business performance.

Key Findings

Fragmented institutional landscape: More than 50 government and semi-government agencies engage in entrepreneurship promotion, resulting in:

- Overlapping mandates

- Duplication of training and financial schemes

- Poor coordination and inconsistent standards

- This complexity confuses beneficiaries and produces inefficiencies in programme delivery.

Beneficiary selection gaps:

Beneficiary selection often prioritizes:

- Welfare eligibility (e.g., Samurdhi status)

- Political referrals

- Institutional convenience

Which leads to mis-targeting, where individuals with limited entrepreneurial readiness are selected, while capable youth and women are excluded.

Input-Driven, One-Size-Fits-all focus:

- EDPs remain heavily input-focused, providing: trainings and one-off equipment or grants.

- Support rarely aligns with: enterprise growth stage, sector-specific requirements’ real business readiness or market demand

Weak Financial and Non-Financial Support Integration:

- Difficulties in accessing certification (GAP, GMP, HACCP)

- Limited assistance with branding and packaging

- Absence of market linkage support

- Minimal help navigating credit and finance schemes

Discrete supports does not translate into improved performance due to missing complementary linkage.

Limited mentoring and monitoring: Most programmes do not include:

- Systematic monitoring

- Regular follow-up

- Embedded coaching

- Data-driven feedback loops

Monitoring is often symbolic, and entrepreneurs lack real-time problem-solving support.

Equity Concerns: Specific groups face additional barriers:

- Youth: lack digital literacy, exposure, collateral

- Women: mobility restrictions, exclusion from networks, institutional bias

- Mid-stage enterprises: outgrow basic EDP support but lack pathways to scale

Existing EDPs are not designed to accommodate these differentiated needs.

Statistical Evidence from SEM

SEM analysis confirms:

- Strong positive links between institutional support, entrepreneurial traits, and enterprise performance.

- Program design factors significantly influence sustainability.

- Without structured and functional support, enterprise growth is limited regardless of individual skills.

These empirical findings indicate that the challenges persist not entirely with entrepreneurs but also with programme design and institutional architecture.

Recommendations

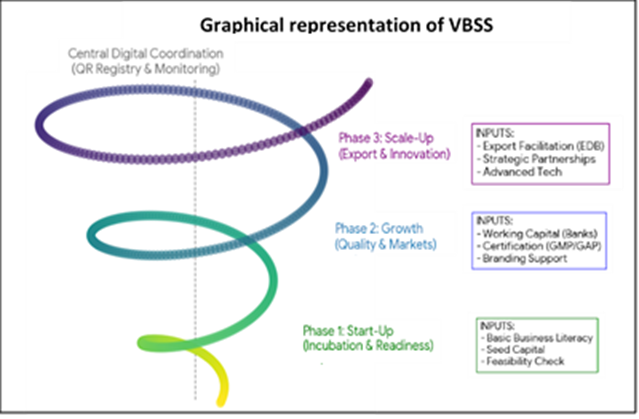

Suggested Model – The Value-Based Spiral Support System (VBSS)

The study proposes a transformative operational model that reconceptualizes entrepreneurship development as a progressive, iterative journey rather than one-off intervention. The Value-Based Spiral Support System (VBSS) ensures entrepreneurs receive stage-appropriate support that evolves with their capacity, enabling upward progression while allowing re-entry for higher-order assistance as businesses mature.

Six Strategic Pillars of VBSS

1. Readiness-Based Beneficiary Selection: Replace welfare-based targeting with dual-criteria assessment combining social equity and entrepreneurial potential. Implement structured interviews and simple business proposals to ensure support reaches both vulnerable populations and high-potential startups while maintaining merit-based allocation.

2. Structured Onboarding and Incubation: Provide comprehensive orientation, feasibility validation, and behavioral training before deploying resources. This preparatory phase ensures entrepreneurs understand business fundamentals, assess market viability, and develop realistic expectations before receiving capital or equipment.

3. Lifecycle-Based Support Tracks: Design differentiated interventions including tailored inputs and guidance for startup (0-1 year), growth (1-3 years), and scale-up (3+ years) phases. Startup support includes basic business literacy, sector-specific technical training, and initial capital. Growth phase emphasizes quality improvement, working capital access, and market expansion. Scale-up focuses on export readiness, certification support, and strategic partnerships.

4. Market and Certification Facilitation: Establish District-level Market and Standards Support Units providing guided certification processes relevant to production and processing industries, branding assistance, buyer-seller networking platforms, trade fair participation support, and export documentation guidance.

5. Monitoring and Embedded Mentoring: Deploy trained Enterprise Development Officers (EnDOs) at the district level, offering continuous performance tracking via digital dashboards, one-on-one coaching addressing operational challenges, adaptive support responding to market changes, and periodic refresher training on emerging technologies.

6. Institutional Coordination and Digital Integration: Create a Central EDP Secretariat within the Ministry of Industries /Agriculture to harmonize EDP’s objectives, prevent duplication, and ensure accountability. Establish District Entrepreneurship Cells (DECs) as decentralized coordination hubs. Implement QR-linked Entrepreneur ID system storing complete intervention history, enabling seamless inter-agency coordination, and generating real-time analytics for evidence-based policy adjustments.

Operationalizing the VBSS – Implementation Roadmap

Immediate Actions (0-12 months):

- Adopt National EDP Framework and establish VBSS principles – for harmonizing objectives, pool resources, and guide all agencies through a unified spiral-based approach.

- Establish Central EDP Secretariat and pilot District Entrepreneurship Cells – for facilitating ground-level responsiveness for certification, mentoring, and market integration.

- Initiate QR-linked digital registry – for transparent tracking, real-time monitoring, and

- Reform selection processes to ensure social inclusion and entrepreneurial capability – for

- Pilot VBSS in 2-3 districts.

Mid-Term Reforms (1-2 years):

Digitize all EDP operations with online applications and automated referrals;

- Scale VBSS nationally with quality assurance;

- Formalize public-private partnerships with exporters, certifiers, and financial institutions;

- Implement performance-based funding tied to outcome metrics;

- Mainstream gender- and youth-sensitive program tracks.

Long-Term Transformation (3-5 years):

- Integrate EDPs with agricultural modernization and export strategies;

- Establish district innovation hubs with laboratories and testing facilities;

- Conduct longitudinal impact evaluations;

- Develop entrepreneurship education pathways in schools and colleges.

Impact Outlook – Enterprise and System-Level Benefits

The implementation of the VBSS is expected to substantially elevate the performance and resilience of agro-based startups by improving business survival beyond the critical early years, enabling enterprises to obtain essential certifications, strengthening their entry into premium and export-oriented markets, and supporting profit growth together with meaningful employment expansion. At the systemic level, the VBSS framework enhances institutional coordination, promotes resource savings, ensures transparency through digital tracking and strengthens performance accountability through clearer institutional roles and specialization. Collectively, these improvements reposition EDPs as dynamic, inclusive, and results-driven mechanisms, capable of transforming fragmented, grant-led programmes into strategic drivers of agricultural modernization, rural youth engagement, women’s economic empowerment, and national economic resilience.